Northern Mariana Islands (Mariana Archipelago)

The US Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) and the Territory of Guam comprise the Mariana Archipelago. Archaeological research has revealed evidence of fishing in the Mariana Archipelago dating back three millennia, showcasing the integral role that the surrounding ocean waters played in the everyday lives of its citizens. Occupations by the Spanish, Germans, Japanese and the United States significantly changed the composition of fishing activities throughout the archipelago, ultimately generating the conditions in the local shore- and boat-based fisheries observed today. The resources supported by the marine environment are still depended on by locals for sustenance and cultural activities.

Overview

The Mariana Archipelago is located on the other side of the dateline from the rest of the United States in the part of Oceania known as Micronesia. It is comprised of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) and the US Territory of Guam, which are more closely related in heritage and tradition to other Micronesian archipelagos than to the United States. The CNMI and Guam shared a common geography, political status, history, culture and economy until 1898, when the archipelago was politically divided.

The archipelago’s indigenous Chamorro and Refaluwasch communities have a history of fishing that spans over three millennia. Waves of colonization by Westerners beginning in the 1600s had a devastating impact on traditional fishing practices. Today, the expansion and development of fisheries are still constrained, and most of the fishermen in the archipelago participating in the bottomfish, crustacean and coral reef ecosystem fisheries do so primarily for subsistence, barter and, cultural sharing purposes, such as for fiestas and food exchanges with family and friends.

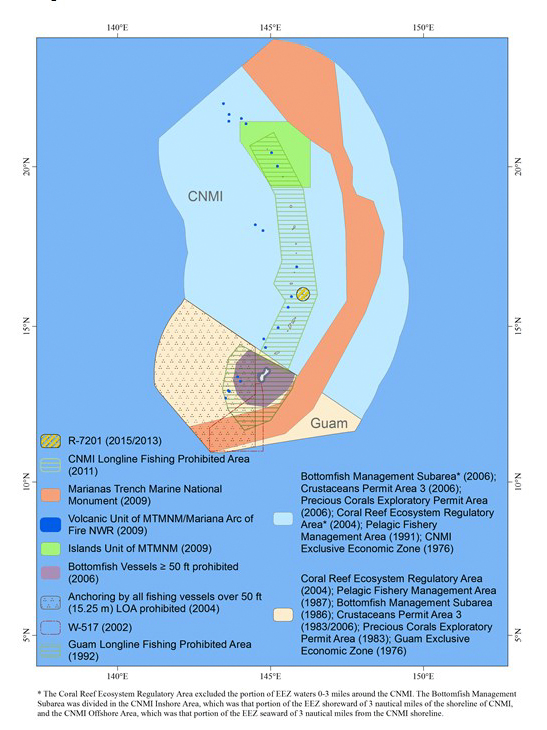

In CNMI, waters 0 to 3 miles from shore are managed by the Territory except in areas near Tinian and Farallon de Medinilla where US forces conduct military training and around Farallon de Pajaros (Uracas), Maug, and Asuncion in the Marianas Trench Marine National Monument until coordinated management plans can be developed to protect these resources. These specified waters 0 to 3 miles from shore as well as waters 3 to 200 miles are federally managed.

Enforcement of federal fishery regulations is handled through a joint federal-territorial partnership. Annual reports on the fisheries are produced by the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, with data collection responsibilities shared by various territorial and federal agencies.

The surrounding waters of the Mariana Archipelago play an integral role in the everyday lives of its citizens. The ocean is a major source of food and leisure activities for residents and tourists alike. Fisheries development prospered during the Japanese administration in the 1910s, becoming the nation’s second largest industry as small pelagic fishing operations were established and the Garapan port became the main area for drying fish. The fishing industry was destroyed during World War II but quickly rebuilt afterwards with support from the US military. Okinawans who operated the fishery prior to the war were hired to operate and train locals to fish commercially, targeting pelagic species. Nowadays, small-scale troll, bottom and reef fish fisheries persist, with landings sold locally. Although the composition of fishing activities has changed significantly, a common view of its importance remains. The waters around the CNMI are extensive and contain abundant fisheries resources. Fisheries development potential for underutilized bottomfish and pelagic species is substantial.

The status of the fisheries is updated annually in the Council’s Annual Reports for its Fishery Ecosystem Plans.

CNMI Fisheries

Fisheries in the CNMI have generally been relatively small and fluid, with 16 to 20 foot boats fishing within 20 miles from Saipan. Many of these small vessels conduct multiple fishing activities during a single trip (e.g., a company supported mainly by troll fishing may also bottomfish and spearfish to supplement its income).

Fishing businesses tend to enter and exit the fishery when it is economically beneficial to do so, as they are highly sensitive to changes in the economy, development, population and regulations.

Subsistence fishing continues; however, fishing methods and target species have shifted in step with population demographics and fishery restrictions. Nearshore hook and line, cast net and spear fishing are common activities, but fishing methods such as gill net, surround net, drag net and SCUBA-spear have been restricted or outright banned in the CNMI since the early 2000s.

Pelagic Fisheries

The CNMI’s pelagic fisheries occur primarily from the island of Farallon de Medinilla south to the Island of Rota. The number of boats involved in CNMI’s pelagic fishery has been steadily decreasing since 2001, when there were 113 fishermen reporting commercial pelagic landings.

The number of fishers reporting pelagic landings has been highly variable in recent years. In 2016, a decade-high of 63 fishermen reported landings, a significant increase from 12 in the previous year. However, 40 fishers reported pelagic landings in 2018.

Total pelagic landings in 2018 were 367,473 pounds, an 8 percent increase from 2017 levels. Commercial revenues were $366,553 in 2018 based the commercial receipts.

Island Fisheries

Bottomfish

In the CNMI, bottomfish catch in 2023 for both bottomfish management unit species (BMUS) and all species caught by bottomfishing gear decreased by approximately 64.63 percent from 2022 (36,094 pounds).

2023 federal permit data show that there was one bottomfish permit holder in the CNMI and no active federal permits for lobster or shrimp.

Stock assessment parameters for the CNMI BMUS complexes generated by Langseth et al. (2019) suggest that the complexes are not overfished, nor are they experiencing overfishing.

Non-Commercial Fisheries

Fishing non-commercially (for recreation, sustenance, subsistence, cultural exchange, etc.) is done through both boat-based and shore-based methods. Most of the fish is either consumed or given away. Non-commercial fishing trips target mainly fish for pelagic species such as skipjack tuna and dorado, but will also fish for bottomfish and reef fish (including rabbitfish, parrotfish and emperors). Charter fishing in the CNMI is limited.

Ecosystem Components

National Standard 1 allows for the Regional Fishery Management Councils to identify species, species complexes, and stocks that would constitute Ecosystem Components (81 FR 71858, October 18, 2016). Ecosystem Components are species that contributes to the ecological functions of the island fisheries ecosystem. These species are retained in the Marianas FEP for monitoring purposes and are protected associated with its role in the ecosystem and to address other ecosystem issues.

Coral Reef Ecosystem Component Fisheries

In the CNMI, recorded coral reef ecosystem management unit species (CREMUS) catch in 2023 totaled 654 pounds, showing a continued decline compared to historical levels. In 2023, the bigeye scad (atulai, Selar crumenophthalmus) topped the list of the most landed ecosystem component species (ECS) in CNMI, with 6,851 lbs recorded in creel surveys and 9,687 lbs in commercial landings, maintaining a trend similar to 2022. Surgeonfish ranked second in creel survey data, while parrotfish was the second most landed species in commercial reports. Participation in the coral reef fisheries of CNMI declined in 2023 by one vessel, with 12 vessels involved with boat-based spearfishing.

Crustacean Ecosystem Components

In the CNMI, catch for the crustacean fishery has been limited to several hundred pounds per year, with no active fishery for deep-water shrimp. In 2023, there was no recorded catch of slipper lobster or other crustaceans in the CNMI, based on available federal logbook data.

Precious Coral Ecosystem Components

Regulations require this permit for anyone harvesting or landing black, bamboo, pink, red or gold corals in the US EEZ in the Western Pacific. In the CNMI, there has similarly been no record of special coral reef or precious coral fishery permits issued for the EEZ around the Northern Mariana Islands since 2007. The status of the fisheries is updated annually in the Council’s Annual Reports for its Fishery Ecosystem Plans. For complete information on the current status of the fisheries, please see the Annual Reports:

Fishery Issues

Fisheries in the Mariana Archipelago are dynamic and always changing. Click here to see which issues the Council is working on in the Mariana fisheries and what other fishery issues are impacting the Mariana Archipelago.

Fishery Ecosystem Plans

The MSA authorizes fishery management councils to create fishery management plans. The Western Pacific Council’s plans utilize an ecosystem-based approach and are place-based Fishery Ecosystem Plans (FEPs). The FEPs establish the framework under which the Council will manage fishery resources. An overall Pacific Pelagic FEP was created because of the migratory nature of the pelagic species. Both the Mariana Archipelago (CNMI and Guam) and Pelagic FEPs were approved in 2009 and codified in 2010. These FEPs have been, and continue to be, amended as necessary.

Ecosystems + Habitat

Regulations + Enforcement

Protected Species

Quotas + Annual Catch Limits

Marine Conservation Plans

Marine Conservation Plans (MCPs) are required by the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (Section 204(4)) detailing the use of funds collected by the Secretary of Commerce pursuant to fishery agreements (e.g. Pacific Insular Area fishery agreement, quota transfer agreement, etc.). These MCPs should be consistent with the fishery ecosystem plan, identify conservation and management objectives, and prioritize planned marine conservation projects. The MCPs are developed by the Governor of each territory/commonwealth and is applicable for three-years. Click below for CNMI’s latest Marine Conservation Plan

Projects and Publications

The Council has done a lot of work with the fisheries of the Mariana Archipelago from research, to workshops, to outreach and education. Below are some of the completed projects and publications.

- Council staff. 2014. Disproportionate burden workshop

- Council staff. 2014. Territorial fisheries staff issues and needs

- Markrich, M. August 2013. Managing Sustainable Shark Fishing in the Mariana Archipelago

- Bak, S. February 2012. Evaluation of Creel Survey Program in the Western Pacific Region (Guam, CNMI and American Samoa)

- Walker R, Ballou L and Wolfford B. 2011. Non-Commercial Coral Reef Fishery Assessments for the Western Pacific Region

- Luck, D., & Dalzell, P. (2010). Western Pacific Region Reef Fish Trends: A Compendium of Ecological and Fishery Statistics for Reef Fishes in American Samoa, Hawai’i and the Mariana Archipelago in Support of Annual Catch Limit (ACL) Implementation (Tech.). Honolulu, HI: Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council.

- Luck & Dalzell Appendices

- Miller et al. 2001. Proceedings of the 1998 Pacific Island Gamefish Symposium: Facing the Challenges of Resource Conservation, Sustainable Development, and the Sportfishing Ethic. (29 July-1 August 1998, Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, USA)

- Amesbury, J. 1989. Native Fishing Rights and Limited Entry in the CNMI.

Indigenous Resources

Since its inception in 1976, the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council has been guided by the social, cultural and economic realities of our island communities. In our region, since time immemorial, the ocean has been the primary source of protein. Conservation was the system for food security and survival.