American Samoa Archipelago

The only US territory south of the equator, American Samoa has a history of fishing that spans more than three millennia. Today, fishing in the territory is shaped by traditional Samoan values that exert a strong influence on when and why people fish, how they distribute their catch and the meaning of fish within the society.

Overview

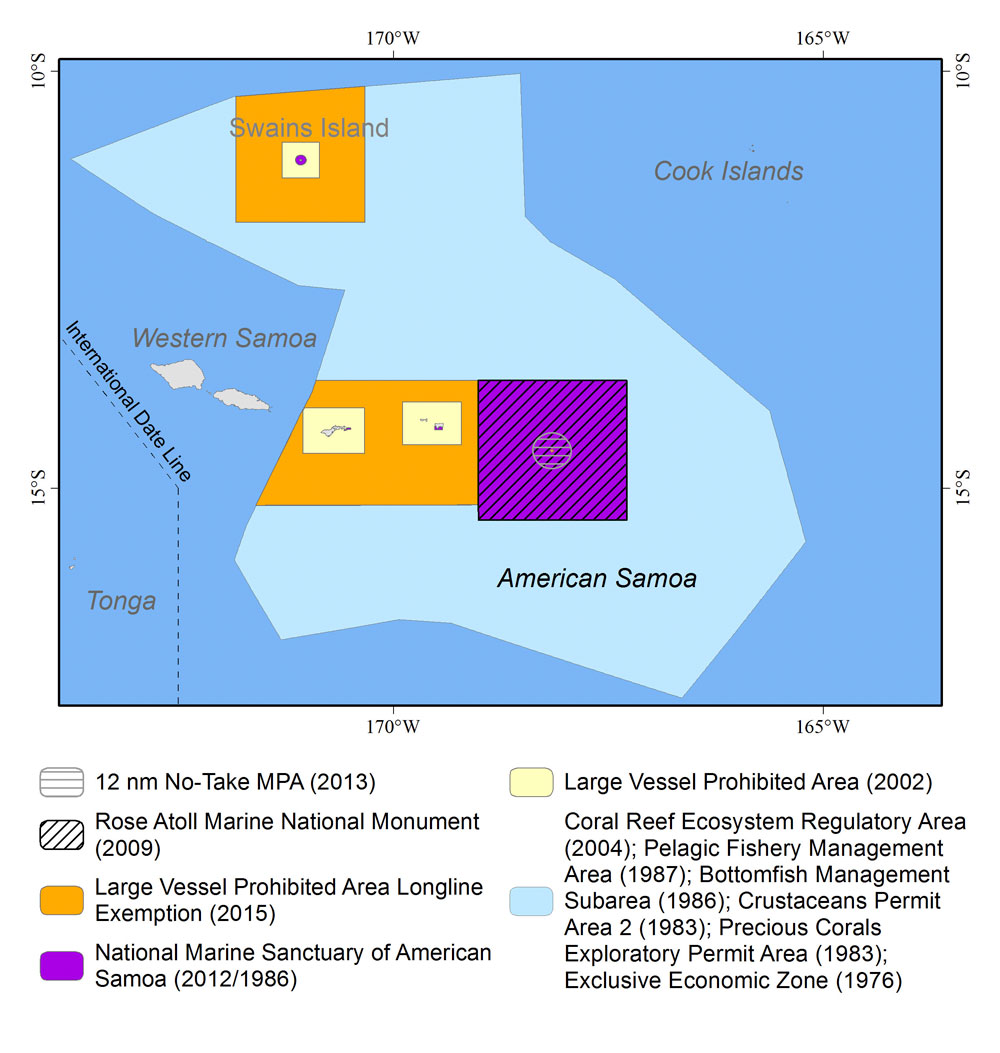

The American Samoa archipelago is located halfway between Hawaii and New Zealand, consists of five volcanic islands and two coral atolls—Tutuila, Aunuu, Rose, Swains and the Manu’a group of Tau, Olosega and Ofu. American Samoa’s dependence on fishing goes back about 3,500 years when people first inhabited the Samoan archipelago. When distributed, fish and other resources move through a complex and culturally embedded exchange system that supports the food needs of aiga (extended family) as well as the status of both matai (chiefs) and village ministers.

Traditional harvest of deepwater bottomfish, prior to Western contact, included the use of canoes, hand-woven sennit lines with stone sinkers and hooks from pearl shell. Cultural distribution included chiefs, chiefs’ wives and young untitled men. By the 1950s, many small bottomfish operations were equipped with outboard engines, steel hooks and linen and monofilament fishing lines. In the early 1970s, the commercial bottomfish fishery began developing supported by a government-subsidized program that provided local fishermen with gasoline and 23 diesel powered 24–foot wooden dories capable of fishing in offshore waters. By 1980, mechanical problems and other difficulties reduced the fleet to one vessel.

In the early 1980s, the fleet size recovered when local boat builders began constructing the inexpensive but seaworthy 28-foot alia fishing catamaran, designed by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. This, along with a government-subsidized project to export deep-water snapper to Hawaii, caused another notable increase in bottomfish landings. Between 1982 and 1988, the bottomfish fishery peaked at almost 50 vessels landing over 100,000 pounds annually. Bottomfish accounted for as much as half of the total catch of the local commercial fishery.

Skipjack tuna, known locally as atu, is another important species both nutritionally and culturally. The methods and equipment for catching skipjack have changed, but the fish brought to shore continue to be distributed within Samoan villages according to age-old ceremonial traditions. Beginning in 1988, longlining for pelagic species, such as tuna, overtook bottomfish fishing as American Samoa’s main commercial fishery.

American Samoa is considered “unincorporated” because the US Constitution does not apply in full. The primacy of Samoan custom over all sources of traditional law is recognized by the Samoan Constitution (enacted in 1967), by the Tripartite Convention of 1899 that created the territory and by subsequent amendments and authority.

Current American Samoa Fisheries

American Samoa’s domestic commercial fishery consists of a fleet of mostly longline vessels in the pelagic fishery (principally, albacore tuna) and some part-time smaller vessels in the bottomfish fishery. The subsistence and small-scale commercial coral reef fishery and crustacean fishery employ various gear types including hook and line, spear gun and gillnets.

The status of the fisheries is updated annually in the Council’s Annual Reports for its Fishery Ecosystem Plans. For complete information on the current status of the fisheries, please see the Annual Reports:

Pelagic Fisheries Status

The largest fishery based in American Samoa is its longline fishery. The longline fleet consists of eight vessels greater than 70 feet in length, four vessels between 50 and 70 feet in length and one vessel less than 40 feet in length. Smaller longline vessels called alias (locally built, twin-hulled vessels up to 30 feet long, powered by 40 horsepower gasoline outboard engines) can fish within 50 nautical miles from shore.

Pelagic landings consist mainly of five tuna species including albacore, yellowfin, skipjack, mackerel, and bigeye, which made up approximately 95 percent of the total estimated landings when combined with other tuna species. Wahoo, blue marlin and mahimahi made up most of the non-tuna species landings.

In 2018, there were 13 active longline vessels, although the fleet has been gradually declining since 2008 when the fleet was nearly double the current size (in numbers and catch). Due to low participation (less than three), the alia data are confidential and are reported only as combined with the large vessel fishery. Troll and handline fishing are the next largest fisheries with seven boats landing pelagic species in 2017. Recreational pelagic fisheries in this region are less common.

Estimated total landings in 2018 for American Samoa pelagic fisheries were approximately 4.1 million pounds, declining since 2009 and 2010 when landings exceeded 11 million pounds. In 2018, a total of 3,122,082 pounds of albacore were caught by the American Samoa longline fleet, making up 76 percent the tuna species in total estimated landings. Yellowfin tuna catch by the fleet was in 2018 was 542,078 pounds.

Despite a precipitous decline in targeted tuna catches by the American Samoa longline fleet since 2010, stock assessments of yellowfin tuna and South Pacific albacore indicate that the stocks are not overfished and that overfishing is not occurring. In 2017, total catches of South Pacific albacore and yellowfin tuna within the Western and Central Pacific Ocean were at record high levels, due to the combined harvests of several international fisheries. US purse-seine vessels also homeport out of Pago Pago harbor and deliver skipjack, yellowfin and bigeye to the local cannery.

Purse-seine fishing, when conducted in the US exclusive economic zone, can be regulated by the Council, but to date, there are no specific purse-seine regulations under the Council’s Pelagic Fishery Ecosystem Plan. The US purse-seine fishery is regulated by the US government under the South Pacific Tuna Treaty and the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission Implementation Act.

Island Fisheries Status

Bottomfish

The bottomfish fishery landings in American Samoa, relative to the short-term average, declined in 2018. Considering only bottomfish management unit species (BMUS) on a short-term basis, total estimated catch decreased by 30 percent while the commercial landings decreased by 34 percent. This indicates that the majority of the BMUS catch was non-commercial. The amount of effort in the bottomfish fishery (measured in gear-hours) decreased by 59 percent in 2018 relative to average values from the last decade, while the total number of participants decreased by 11 percent compared to the short-term average.

Non-Commercial Fisheries

Non-commercial fisheries in American Samoa include small-scale fishing for pelagics, bottomfish and coral reef fish for subisstence, social and cultural purposes for food, cultural exchange and recreation. Most fishing in American Samoa is done non-commercially and boat-based recreational fishing in American Samoa has been influenced by the fortunes of fishing clubs and fishing tournaments. There is no full-time charter fishery in American Samoa, but there are for-hire services offered.

Ecosystem Components

National Standard 1 allows for the Regional Fishery Management Councils to identify species, species complexes, and stocks that would constitute Ecosystem Components (81 FR 71858, October 18, 2016). Ecosystem Components are species that contributes to the ecological functions of the island fisheries ecosystem. These species are retained in the American Samoa FEP for monitoring purposes and are protected associated with its role in the ecosystem and to address other ecosystem issues.

Coral Reef Ecosystem Component Fisheries

Coral reef fishery catch in 2018 from the boat-based fisheries in American Samoa was 62 percent lower than the short-term average which continues a two-decade decreasing trend. The shore-based coral reef fisheries had an estimated catch in 2018 that was 61 percent lower than the short-term average catch. The catch per unit effort (CPUE) in the coral reef boat-based fisheries was higher in the mixed bottomfishing and trolling methods than in the spearfishing method over the same time period. Trolling CPUE had decreased 55 percent in 2018 in the midst of a 10-year increasing trend. The shore-based gleaning fishery showed a lower estimated CPUE, whereas the spear, rod-and-reel and gill net fisheries had higher CPUE. Fishing effort values were lower in 2018 for five coral reef fishery methods than the previous year. Boat-based spear, mixed bottomfishing-trolling and shore-based rod-and-reel each had a lower fishing effort than the short-term average. Data showed that shore-based hook-and-line effort had significantly decreased in 2018 to three total gear-hours (i.e., a 93 percent decrease).

Fishery Issues

Fisheries in the American Samoa Archipelago are dynamic and always changing. Click here to see which issues the Council is working on in the American Samoa fisheries and what other fishery issues are impacting American Samoa fisheries.

Fishery Ecosystem Plans

The Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, under authority of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, creates and amends management plans for fisheries seaward of state/territorial waters in the US Pacific Islands. The Western Pacific Council’s Fishery Ecosystem Plans (FEPs) are place-based and utilize an ecosystem approach. An overall Pacific Pelagic FEP was created because of the migratory nature of the pelagic species. Both the American Samoa Archipelago and Pelagic FEPs were approved in 2009 and codified in 2010. These FEPs are amended as necessary.

Ecosystems + Habitat

Regulations + Enforcement

Protected Species

Quotas + Annual Catch Limits

Marine Conservation Plans

Marine Conservation Plans (MCPs) are required by the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (Section 204(4)) detailing the use of funds collected by the Secretary of Commerce pursuant to fishery agreements (e.g. Pacific Insular Area fishery agreement, quota transfer agreement, etc.). These MCPs should be consistent with the fishery ecosystem plan, identify conservation and management objectives, and prioritize planned marine conservation projects. The MCPs are developed by the Governor of each territory and is applicable for three-years. Click below for American Samoa’s latest Marine Conservation Plan

Projects and Publications

The Council has done a lot of work in the American Samoa Archipelago fisheries from research, to workshops, to outreach and education. Below are some of the completed projects and publications.

- Council staff. 2014. Territorial fisheries staff issues and needs

- Fa’asili. 2014. AS fishermen training program

- Fa’asili. 2014. AS multipurpose fishing boat report

- Fa’asili. 2014. Fishermen lending scheme

- Bak, S. February 2012. Evaluation of Creel Survey Program in the Western Pacific Region (Guam, CNMI and American Samoa)

- Ochaville. 2012. Ecosystem indicators for the coral reef fisheries in ASindd

- Walker R, Ballou L and Wolfford B. Non-Commercial Coral Reef Fishery Assessments for the Western Pacific Region

- Luck, D., & Dalzell, P. (2010). Western Pacific Region Reef Fish Trends: A Compendium of Ecological and Fishery Statistics for Reef Fishes in American Samoa, Hawai’i and the Mariana Archipelago in Support of Annual Catch Limit (ACL) Implementation (Tech.). Honolulu, HI: Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council.

- Luck & Dalzell Appendices

- Sabater. 2010. Mapping and Assessing critical habitats

- Wiles et al. 2010. Current Surveys between Potential Marine Managed Areas in Am Samoa

- Council Staff. 2006. Summary Report: South Pacific Albacore longline Fisheries workshop

- Miller et al. 2001. Proceedings of the 1998 Pacific Island Gamefish Symposium: Facing the Challenges of Resource Conservation, Sustainable Development, and the Sportfishing Ethic. (29 July-1 August 1998, Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, USA)

- Severance, C., & Franco, R. 1989. Justification and Design of Limited Entry Alternatives for the Offshore Fisheries of American Samoa, and an Examination of Preferential Fishing Rights for Native People of American Samoa within a Limited Entry Context.

Indigenous Resources

Since its inception in 1976 the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council has been guided by the social, cultural and economic realities of our island communities. In our region, since time immemorial, the ocean has been the primary source of protein. Conservation was the system for food security and survival.